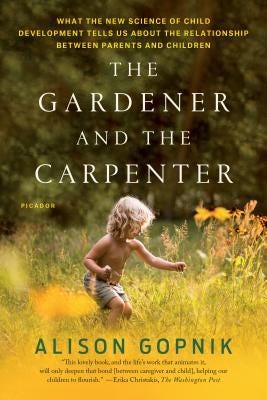

Alison Gopnik's The Gardener and the Carpenter - A Short Review

I recently finished reading Alison Gopnik's The Gardener and the Carpenter after hearing an interview with her on the Hidden Brain podcast. While the book had its weaker parts and forays into the weeds of evolution and child development, the central premise is certainly important for any of us who are raising or teaching children.

The title of the book sets up the dichotomy of "parenting" versus being a parent. Gopnik sets up the central premise by briefly exploring the usage of "parent" as a verb rather than a noun. "To parent", Gopnik writes, makes about as much sense as "to child" or "to wife". Someone is a parent rather than a job that a parent does. In Gopnik's eyes, using "parent" as a verb means treating it more as a job. She further fleshes out this idea by giving us the contrasting work of a gardener and a carpenter. A carpenter's work follows a plan and has a measurable outcome. A carpenter is striving to create, say, a chair so the end product should be a functional chair that resembles the plans the carpenter followed. This method, according to Gopnik, is what "parenting" looks like. We choose a plan for a child and work towards the fulfillment of that plan. We will do everything we can to follow that plan, which we think of as doing everything for the sake of giving the child "every opportunity to be successful" or some equivalent statement. We may not recognize the subtle shift from doing everything for the child to doing everything for the plan. We and others will ultimately determine our parenting success by measuring the difference between the plan and the grown child. Gopnik contrasts this with the work of the gardener. The gardener admits that he or she exerts far less control over the garden in his or her care. We can plant, water, and fertilize to the best of our abilities but the plants are subject to factors outside of our control. And even within what we can control, the plants still have their own say. The flowers do not grow on the trellis we set up for them. The strawberries are not as large as we had hoped. But the good gardener accepts that this is how gardening goes and keeps tending the garden and seeing what happens next. So as parents, we must have patience not just with our children but with ourselves as we recognize that we do not have the control that we imagine. The goal is not a final product but growth.

Gopnik spends time describing research in child development and anthropology that demonstrate how children's brains work best and how other animals and societies have raised their young in ways that optimize that mental development. The examples can seem anecdotal or esoteric at times but they serve the goal of reinforcing that "parenting" is less optimal than "being a parent" as described above.

The most salient message in the body of the book is that play is about exploration rather than exploitation. Exploration is about creating possibilities and may not have an end goal in mind. Play gives children opportunities to figure out the world around them and how they can affect that world. Exploitation is generally goal-oriented and is intended to use what we already know in order to advance in some way. Gopnik is telling us that there are times for each and that as parents and caregivers, we should choose judiciously between the two for those in our care. We recognize that play has long been formalized for adults, primarily in the form of competition. Our play involves winners, losers, and indicators of performance and progress. Gopnik points out that we are now formalizing the play of our children to greater and greater extents. This is not indicated just in the prevalence of competitive youth sport but in other facets of life where we give children toys for "edutainment" or the like. Everything our children do has to have a goal of advancing them in some way. Gopnik reminds us that no it doesn't. Play is about growing rather than goal attainment. The pruning of possibilities comes after the realization that there are many possibilities and the expansion of those possibilities. This isn't an indictment of youth sport but a reminder that not all play should be sport. We fail to recognize that our adult goal-oriented mentality, in many settings, actually hinders learning in children.

I enjoyed this book for separate reasons. The meticulous explanations of scholarly work, complete with extensive notes and bibliography, attracted the scientist in me that wants to know the science and history behind learning and child development. The larger themes of what it means to learn, to play, and to be a parent were attractive to me for different but perhaps more satisfactory reasons. If only one of these areas is interesting to you then the book may be less enjoyable but still worthwhile in my opinion. To get the most out of it, it helps to be both a scholar and a parent, like Gopnik is but don't let that stop you from reading it, as it is well written and enjoyable for any caregiver or invested person.