Drills in Depth - Tic Tac Toe with Alex Luna

Playing games within the game

Alex Luna has a lot of thoughts in his head. Whatever it is that he’s doing, rest assured that he’s thinking about it. Maybe he’s thinking about how to beat the game he’s playing, maybe he’s thinking about how to get more out of the practice plans he’s writing. What I appreciate about all that thinking is that it represents a trait I think is invaluable to coaches, reflection. Alex is currently an assistant coach for South Carolina’s beach volleyball team.

What are Drills in Depth? - Read here

Who: Alex plays this game with his NCAA women’s beach team but, as you’ll see, the nature of the game makes it easily adaptable to almost any age or skill group. There’s no reason why the game couldn’t be adapted for indoor teams as well. The game can be structured to reward plays as simple as “pass-set-hit” while also supporting multi-layered play as complex as you can imagine.

What: Tic Tac Toe is a regular game of volleyball with an additional scoring system that runs in parallel to the regular score of the game. Alex mostly plays games to 15 when using Tic Tac Toe but he will have teams play to 21 if they are using the “blackout” variation (see below). Either way, teams must either win by two on the regular scoreboard or win the Tic Tac Toe game, whichever comes first. Rallies are played normally and teams are trying to win the rally and/or satisfy criteria on the Tic Tac Toe board during the rally.

When: Tic Tac Toe can be played at any point in a season. Alex said it’s a way to play more without ignoring your focal points so it can be used at any point in a season by making the tic tac toe board relevant to what players are working on at that point. Alex talked about using it later in practice, “on the way towards more game-like stuff”. In a college beach practice setting, there are usually multiple courts in use so all courts would be playing Tic Tac Toe at the same time. But, Alex also uses the game at different times in practice. As an example of this, he introduced me to the idea of “micro-dosing competition” by playing shorter games at different points in practice. Alex will use one court for short Tic Tac Toe games while other courts may be used for training different skills. Ultimately, Alex said that he didn’t want to fall into the trap of “train, train, train” and then just play at the end of a practice session. Mixing games in earlier in practice helps him do that.

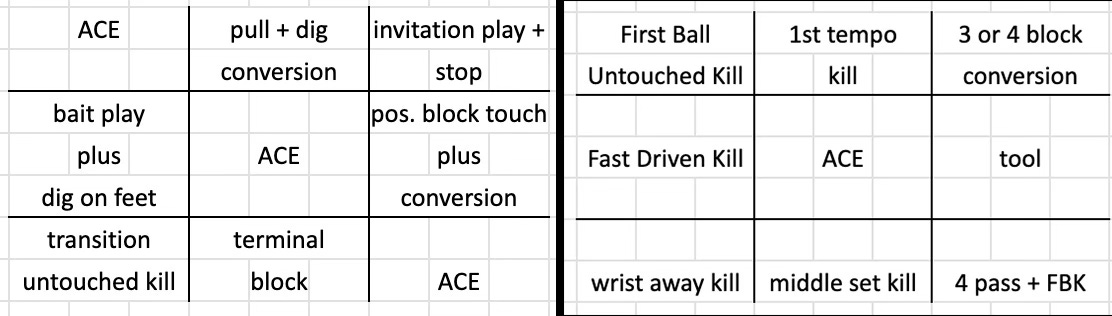

How: What makes Tic Tac Toe interesting is the board. Alex creates boards with different objectives for teams to achieve while playing. The boards are laid out in a Tic Tac Toe grid. Here are a couple of examples Alex shared with me.

In the game’s simplest version, there’s a single dry erase board, sitting courtside, on which the teams on the court are playing against each other. While they are playing a set to 15, they are trying to meet some of the objectives on the board. On the board, the teams are trying to win a game of tic tac toe, meaning that each team is trying to complete a row, a column, or a diagonal while trying to block their opponents from doing the same. A team takes a square by successfully completing the objective in the square during a rally. That team marks the square as theirs (Alex uses magnets to mark the squares) after the rally and then play continues. Play continues until a team wins the set to 15 (by at least two points) or gets tic tac toe on the board.

There are two additional rules that shape how the game is played. First, Alex always includes at least one ace on each board because he always wants players to serve tough. The way he makes sure that players keep serving tough, even after a team has taken an ace square, is to make all ace squares “stealable”. This means that one team can take over an ace square that belonged to their opponent by serving an ace after them. Second, teams must immediately call out what they did to score, even in the middle of a rally if their objective is not a terminal play. Without the rule, players would check the board after winning a rally to see if they had done something that also appeared on the board. Alex likes this rule because it keeps teams from playing mindlessly if they want to take squares on the board.

Alex has a few variations that he uses in Tic Tac Toe. Instead of playing with a single tic tac toe board for both teams, sometimes each team has their own board. When using two boards, there’s no opportunity to block your opponent on the board so both teams are trying to complete every objective on their board. (This is the “blackout” variation.) Since there are more objectives to hit, games are played to 21 instead of 15 in this variation. Another variation is to make all squares “stealable” instead of just aces. This prevents teams from ignoring objectives after they’ve been done or forgetting to defend against those same objectives. Sometimes Alex will add penalties for errors, when he does that he’ll usually allow an opponent to remove a piece from a opponent’s board after they make two consecutive unforced errors.

The Depth

Who: At South Carolina, Alex is in charge of practice planning so during a practice you are likely to see him roaming from court to court. Although, given the way most collegiate beach practices are structured, coaches often have to circulate anyways. For Alex, the roaming helps him stay aware of how practice is flowing so he can make adjustments or make mental notes for planning future sessions. When Tic Tac Toe is being played, he will sometimes make comments to pairs as he moves around. He likes to nudge them to look at the board more to develop their awareness of what scoring opportunities exist from one point to the next. He doesn’t like to give too much feedback because, in his words, “I don’t like thinking that players are reliant on my voice.” To that end, his feedback tends to be in the form of questions about tactics or about how different movements feel. “I like things where the feedback comes from the structure of the game,” he told me. But, he won’t hesitate to bring it up when a pair misses a scoring opportunity because they didn’t recognize it, like when they do something that is on the board but don’t call it out when it happens. Ultimately, Alex likes the dual ways of winning because it allows teams to play their own way to victory rather than having their style of play dictated to them by the coaches.

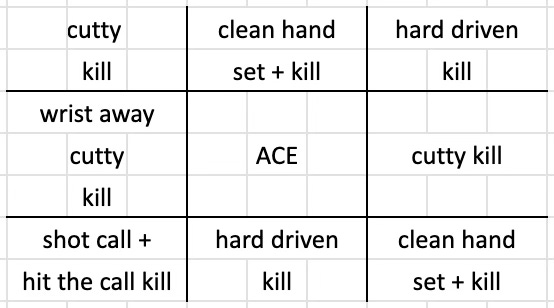

What: For Alex, the coaching he does for Tic Tac Toe isn’t during play, it’s in the way he builds the boards that are used during the games. He draws up new boards regularly to reflect current objectives or skills that the whole team has been working on. When he “micro-doses” competition, the boards will contain objectives that incorporate skills and tactics that teams were working on immediately prior to playing. When pairs are playing the two-board version, the boards will reflect either objectives that play to each pairs’ strengths or that stretch each pair in specially tailored ways. An example of this is when a pair is first playing together and they are figuring out what their strengths and team identity will be. When he does this, the boards look a little different. To emphasize the relevant tactics without having them get lost in the mix, Alex reduces the number of unique objectives and repeats each one. Here’s an example.

Repeating items forces pairs to do those things repeatedly within a game, which is a great way to keep players hunting for opportunities to execute. Another important aspect of creating Tic Tac Toe boards is learning where to place different objectives relative to one another. Alex pays attention to how easily pairs can get three objectives in a row in order to prevent games from either ending quickly or being lopsided. Where objectives are located on the board changes how teams play the game as they search for ways to connect objectives efficiently. While placing items on the boards may be an acquired skill, Alex has a clear way to create items. He says that he works backwards from the demands of the game to decide which objectives should appear on the board and how frequently they should appear. An example of this is what I mentioned earlier, that “ace” appears on every board and is always “stealable”. Because Alex thinks that serving pressure is an important demand in the game, the boards he builds reflect that value.

When: Usually this section serves to describe how a coach adapts their activity to use it at different times in a practice or in a season but not today. Perhaps the most interesting “when” in Tic Tac Toe is much more about strategy than it is about session planning. Remember that there are essentially two ways to win a single game of Tic Tac Toe, a team can win on the objective board or on the actual scoreboard. Because of this, Alex pays attention to when teams choose to ignore the tic tac toe board and only play to win on the scoreboard. There’s no right answer but it’s intriguing to observe how pairs view their chances of winning one way versus winning the other. There are tradeoffs to be considered at every moment, just as there are in actual matches. Should we try something that we’re not as comfortable doing because it might have a better chance of scoring or should we opt for being really good at what we’re already really good at? What are our opponents doing against us? If they’re playing the tic tac toe board, can we just race to 15 while they inefficiently try to complete a row? Can we do just enough to block them (like with an ace?) while just playing to win regular points? If they’re playing straight too, can we still beat them? Alex believes that elite players are holding many strategic ideas in their minds all the time. For Alex, observing pairs work through all the different strategic options in between points is an important way to see how players are viewing the game and competing. Sometimes, he says, there are players that “don’t think like that at all,” they seem oblivious to all the scheming. When players don’t seem to be thinking strategically or when he thinks players might be thinking a little too strategically, Alex will throw a wrench in the works. He’ll comment loudly to one pair (so the other pair can hear) about the other team’s strategy, it’s his way of engaging players more deeply and of balancing out games.

How: Alex has a fascinating question that drives how he interacts with players during practice. To shape how he talks, he’ll often ask himself, “how would I coach this player if I didn’t speak the same language as they do?” The question forces him to think about how clearly, cleanly, and simply he can give feedback. He doesn’t want to allow himself the luxury of just talking until he feels like something sticks in the players’ heads. He would rather do the work to distill a lot of words down to the essence of what must be communicated. This way of thinking is echoed in a key question that describes the lens through which he watches play, “how clean is their volleyball?” This question is not another way of asking if a pair is playing “perfectly”, where every contact goes exactly where it is supposed to go. “How clean is their volleyball?” is asking how simple the play can be and still be effective. Are players giving themselves chances to do what they do best? Are they giving themselves chances to exploit opponent weaknesses? Alex is looking for signs that the players are adapting to the challenges presented in their present matchup. Clean volleyball is when the tools and tactics applied to the situation fit in without wasted physical effort. Ultimately, Tic Tac Toe is a space in which players can experiment and learn what their cleanest volleyball can look like.

Have questions for Alex? You can ask me here or you can email Alex directly. You can also reach out to him on Instagram at coachluna4.