Pavlov’s Dogged Coaches

What does ritualized coaching get you?

You probably learned about turn-of-the-20th-century physiologist Ivan Pavlov at some point. While he was awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on the physiology of digestion, you probably remember him because of an offshoot of that work. During his experiments, he noticed the connection between stimulus and response, contributing greatly to the foundation of Behaviorism in the field of psychology. Pavlov noticed that the dogs he was studying salivated when food was brought to them. Further, he noticed that, over time, when the dogs saw the assistant that usually fed them, they would also salivate. The dogs had connected the presence of the assistant to the presence of food. The problem becomes clear when the assistant shows up without food. There’s an expected outcome (getting food) based on previous history (the assistant showing up with food). But the dogs didn’t know that the assistant had other reasons for showing up. The dogs’ mistake was connecting the expected outcome with what was, in reality, a neutral stimulus. But let me come back to the present.

I recently read a blog post by Cal Newport in which he discusses how people can derail themselves by mistakenly defining productivity as maximizing inputs instead of as maximizing outputs. He’s saying that their mistake is similar to what Pavlov tricked his experimental dogs into falling for. So what does any of that have to do with coaching?

As Newport pointed out, a mistake modern people make is connecting an expected outcome (increased output) to a neutral stimulus (sitting at your desk, even if you’re not working). Coaches commit this kind of mistake all the time. There are actions coaches take because those actions led to a desired outcome at least once in the past. They’re forgetting the cliché of “correlation isn’t causation”. In some situations, it can be seen as superstition. I’ll call it ritualized behavior. A ritual is something people do that has specific meaning, is done in a specific way, and has a desired outcome. When you do something superstitious, you only sort of believe that your specific, repeated actions will create a desired response. You don’t honestly believe you will win every tournament when you wear your lucky shoes. But there are so many ritualized behaviors coaches engage in with an expectation those behaviors will get a desired outcome.

When a coach uses a negative consequence after player and/or team failure, they are creating a neutral stimulus (the artificial consequence) to accompany the actual stimulus (the failure). The coach will often do this because the actual stimulus isn’t eliciting the response they want. They want players to change their behavior as a result of the failure but they don’t think the players are learning the lesson, so they add something (the consequence) to reinforce the lesson. This is built on the principles of conditioning that Pavlov first brought attention to. Such coaching behaviors are problematic for many reasons, so I won’t dwell on this specific example.

I’ll give you a much more commonplace example, giving feedback to players after they execute a skill. In the motor learning literature, a coach’s feedback is considered “augmented feedback”, meaning what a coach says is additional feedback on top of the feedback intrinsic to the execution itself. The lesson to be learned exists in the action and its outcome, rather than in the words you say afterwards. That means your feedback is a neutral stimulus that may or may not elicit a response. You’re trying to help and, sometimes, it looks like it’s working. These are heartbreaking words for a well-meaning coach to hear. But this is exactly what Newport was writing about, mistaking your inputs for outputs. When coaches give more and/or different feedback, they’re increasing their inputs but what they really want to achieve is better output. You try the same stimulus again and again or you try different stimuli in an effort to get a different response.

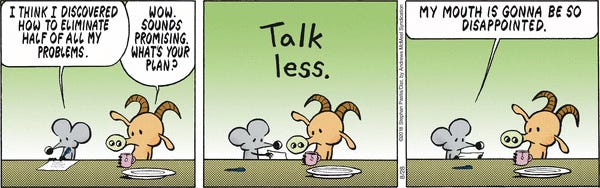

The key to achieving better output isn’t looking for new and better feedback to give because that feedback is still augmenting the existing feedback of the execution itself. The key is less rather than more. Better output can be obtained by helping players interpret the intrinsic feedback better so lessening the amount of neutral stimuli around skill execution will allow players’ attention to go to the sources of information that will help them change their responses. Think of it this way: the situation is talking to you and to the players and your feedback to the players is just more talking. Players have a hard time listening to what the situation is saying to them when they’re listening to you. I view the coach’s job as helping players learn what the situation is saying to them and how to interpret those messages. As a result of this belief, I think coaches’ feedback should have a different focus. If you want to change a player’s response, focus on figuring out what stimulus they’re responding to and help them understand their own stimulus-response connection better.

“Coaching is recognizing situations, [it's] recognizing and responding to the people you are working with.” - Steve Harrison, former Premier League soccer coach

Another behavioral trap coaches fall into is giving feedback at the end of every play or after every rep in practice. This creates a second stimulus-response pairing that interferes with initial pairing from skill execution. When players are being told what to do after each play or rep, they connect the end of a play/rep with being told what to do. They learn to stop paying attention to what just happened so they can pay attention to what the coach is going to say. They learn the coach is the source of information, ignoring the information present in the situation. In this situation, if a play or rep ends without feedback from a coach, the athlete will just await the next play/rep and expect instruction at that time. It’s like if Pavlov’s dogs saw his assistant without food, they would expect the assistant to show up with food the next time. It’s not that players can’t learn or figure things out on their own. They’ve actually learned something all too well: that the coach is the source of all important information about playing. When a coach gives feedback at such a high cadence, they unwittingly teach athletes to not think for themselves, despite the goal of their feedback often being to help players figure out what to do on their own.

But all that focuses on the lessons the players are learning. The point of Newport’s post is to question the lessons you’re learning. You’ve been learning that inputs are more important than outputs. But that’s the cobra effect (which I wrote more about here) at work here because coaches often find themselves chasing inputs/processes as a substitute for the outcomes they really want. Focusing on processes over outcomes is good in that you have far less control over the outcome than you do over the process. The problem arises when you start to believe that the process is all that matters. In particular, you start to believe that your coaching process is all that matters. That’s when you start coaching in a ritualized way. The thought process sounds a lot like this: “if the ball didn’t go where I wanted it to go, I need to address whatever caused the ball to go somewhere else because, if I don’t, the ball will continue to go somewhere other than where I want.” It can be difficult to avoid this trap because you want to believe that what you say has an effect. The problem is the correlation between what you say and what happens afterwards isn’t very tight.

This problem arises because Behaviorism, at a very basic level of understanding, can lead you to believe there is a tight correlation between stimulus and response. But sport (and coaching) aren’t as simple as that; there are many factors affecting outcomes that aren’t part of the stimulus-response model. A lot of that has to do with the world being probabilistic and uncertain. (I wrote about that here.) The first step of getting out of the constant feedback ritual is letting go of the assumption of a consistent relationship between stimulus and response.

Instead of expecting things to change because you said the “right” thing, consider what kind of effect you expect your words to have and how often that effect should appear. Instead of looking for instant and permanent change, consider what positive change could look like and consider how frequently you should expect to see positive changes. (Remember that a loose correlation between stimulus and response means you won’t see changes every time.) Instead of focusing your feedback on the response, find out what the athlete thought the stimulus meant and help them interpret what they saw.

Ultimately, I’m inviting you to reevaluate what you believe effective coaching to be. Does expecting specific responses to specific stimuli allow players to be the best they can be? Does ritualized coaching help you be the best coach you can be? When you decide what you expect the outputs of your coaching to be, you create a much better awareness of what your inputs should be.

Some notes about accuracy and history

When I talk about coaches’ and players’ stimuli and responses, I’m conflating two types of conditioning, classical and operant. Pavlov’s experiments show classical conditioning while B.F. Skinner’s experiments, including those using “Skinner boxes”, show operant conditioning. I think there are elements of both types of conditioning in the examples I use but I think it detracts from the point if I distinguish between the types. The important point is not which kind of conditioning is occurring, but that coaches condition themselves and others by connecting behaviors that aren’t necessarily causally related.

Conditioning studies can be seen as part of Behaviorism, which is a systematic study of behavior that began in the early 1900s. Behaviorism views actions mainly as either being caused by a stimulus from the environment or being a stimulus for behaviors of others further down the causal chain. While there are more modern, robust theories of behavior in psychology, there are elements of Behaviorism that still hold true and have been incorporated into those newer theories and into modern therapies, like behavior modification.

It would be nice to adopt the same language that Cal Newport does in his blog but I don’t feel comfortable referring to the behaviors the same way he and others do. The use of “rain dance”, which refers primarily to Native American traditional ritual dances, as an example of an action of people who don’t understand how science works is problematic because of how it is associated with a single ethnic group that can then be thought of as uneducated or backward. Instead, I chose to focus on the larger phenomenon of ritualized behavior, which doesn’t carry the same connection to a single group of people.

It is hard behavior to change as coach, but I am trying hard to listen more, ask good questions and avoid the endless and often useless feedback. The challenge is that a lot of our players are 'feedback junkies'. They think if the coach is not giving them feedback on every play, they aren't getting coached. Thankfully some of them are beginning to understand that the ball and the play give them feedback and only they know what their actual intention was when they played the ball.