Thoughts on the House Settlement and the Future of College Athletics (part 1)

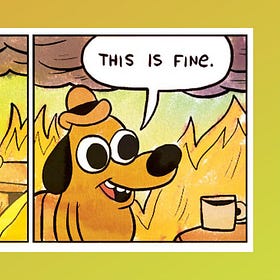

Spoiler: I’m worried...

It’s not my intent to explain the ins and outs of the settlement, I’m doing a bit of speculating and complaining from my specific perspective as a former NCAA Power 4 Olympic sport staff member. If you’d like a bit of an introduction to the House Settlement, here’s as good an article as any from a trusted news source. Also, I don’t have enough experience with Division II or III athletes and institutions to comment on their situations so my thoughts are about Division I only.

As I mentioned in a previous post, I am no longer working at a college volleyball program for the first time in over a decade. I’d be lying if I said that the House Settlement didn’t impact my decision to leave. I believe that, barring major legal and/or legislative changes, the management and administration of Division I sports in the next 5-10 years are barely going to resemble what they do now, unless the sports you’re thinking of are football and a handful of others, depending on where in the country they are.

I think it’s important to make this point clear at the outset. I believe that Division I athletes should get paid. I believe this because of how I’ve seen the demands made on these athletes increase over time. NCAA coaches and administrators have always relied on the argument that athletes are getting paid, in the form of scholarships. I don’t think this argument is very strong anymore because the people in power have increasingly asked more of athletes without increasing how they’ve been compensated in return. While college tuition has increased greatly over time, the practical value of the education, meaning what it is worth to a graduate, has, in my opinion, decreased in that time. So I feel that programs are offering less while demanding more of athletes now than in the recent past. On top of the decreasing value of what programs are offering to athletes, conferences and programs are making much more money today than in the past. Despite this increased profitability, there has never been a mechanism to make any of those profits available to athletes, despite the integral role they play in generating them. It seems to me that there was never any serious discussion about if that was a problem; they are (and always have been) “student-athletes”, so they shouldn’t get paid.

The argument can be made, especially if one sees the NCAA’s recent television commercials, that the NCAA and programs have been making the profits available to athletes via additional support services, Alston money, and, most recently, NIL. I consider it disingenuous to claim these things as profit-sharing for two reasons. First, because all of these are concessions the NCAA was forced to make as the result of legal settlements or losing lawsuits. Second, because they were done, to some extent, to actively avoid paying college athletes for being athletes.

For example, Alston money is generally given to athletes in return for participating in some sort of extra personal/professional/psychological development activities, which is an example of programs asking more of athletes than what they are giving them in return. The money is ostensibly for academic costs and other costs not covered by an athlete’s scholarship. Alston money acknowledges that scholarships don’t cover all the costs of attending school but avoids the uncomfortable truth that programs are ultimately interested in “student-athletes” for their athleticism (read: revenue-generating capabilities) and not for their academic abilities. If institutions were interested in the “student” part of “student-athlete” as much as they cared about the “athlete” part, there would be a host of differences in how athletic departments and teams were administered.

NIL money has provided a way for athletes to profit from who they are as athletes (like from jerseys and endorsements) but still not profit from their actual athletic performances (like from gate receipts or television rights). NIL has allowed the NCAA and programs to simply offload the responsibility of paying athletes for their athletic work to collectives and other outside entities. The athletes and the outside entities that pay them, to keep the NIL payments on the right side of the NCAA, must engage in an actual business transaction, a quid pro quo, of some sort. That means athletes will be doing more than they have been in order to gain the financial benefits of NIL (like filming commercials). It might actually work out better for a college athlete’s time commitments if they don’t have NIL deals because they might be able to benefit from revenue sharing without additional strain. But will they still have access to the same services they currently do? As effects of the settlement begin to appear, many athletic programs are cutting support and service staff. If a program reduces the size of its academic support staff, how will access to services be managed? Will the athletes who bring in the most revenue be given priority? Will access be equally lessened, with richer athletes being invited to hire their own support staff with their new-found wealth? While that follows a pro sports model, is the money the same in a college model?

I acknowledge the problem of paying collegiate athletes for their work is fraught with many confounding factors. Paying them for their athletic and competitive abilities has many implications and consequences and I doubt anyone is completely at ease with any entire set of such consequences. But I think the importance of making changes in this area outweighs the consequences I am uncomfortable with. My feeling on this issue, as with many issues in coaching, is mostly driven by my views on power and autonomy. Money and power are often considered to be tightly bound and this issue is no exception. While the House Settlement appears on its surface to be mostly about money, I think it is important to highlight how shifts in power are also important parts of the issue.

I believe there was a strong motivation for the NCAA and the power conferences to settle rather than to likely lose even more money and power by going to court. But I don’t think they agreed to the terms because they believed college athletes deserved to share in the fruits of their labor. I think the NCAA and its members conceded some things they would have preferred not to but they made those concessions in the name of limiting how much money they would be on the hook for and how much autonomy they might have to concede to the athletes. I believe the NCAA is doing everything they can to avoid losing the unique legal status of “student-athletes”. I think the NCAA would have difficulty justifying its existence if college athletes became employees in the eyes of the law. Instead of being able to continue legislating how member institutions must work with “student-athletes”, that power would be lost to state and federal laws that govern all other workplaces, including the right of employees to unionize. As it stands, the NCAA and its member institutions do not have to collectively negotiate with the athletes (although they increasingly have to negotiate with individual athletes). They can continue to operate paternalistically, as they always have, and continue to say they do so with the best interests of the athletes in mind.

As I mentioned previously, many of the important ways college athletes’ concerns have been addressed has been through the judicial system rather than through direct input from the athletes, despite the existence of student-athlete advisory councils at member institutions. If you review the history of NCAA legislation, there are very few important ones that are products of athlete recommendations. If “student-athletes” were employees, with more direct access to governance, college athletics would be very different than it is now. I think the NCAA and its members were rightly concerned about the size of the workforce they would have to deal with if “student-athletes” suddenly became employees. I recognize that athletes’ lives would change greatly if they became employees but you can tell where the power lies by considering how such changes are discussed with an undertone of “be careful what you wish for”. That’s how those in power try to convince those without it that they shouldn’t want it. I’m not saying there aren’t tradeoffs and difficulties, but I am saying the choice to take on those problems hasn’t been and, to a large extent, still isn’t being given to the athletes.

I think revenue sharing is clearly a large concession, but it still protects the power of the NCAA and its members, especially the power conference programs. That’s why I think the NCAA and the power conferences were more eager to settle than go to court. While the “loss” of revenue to member institutions (because they have to share it) is unpleasant, they were able ensure that amount to be paid out was capped. Even though institutions now have to share revenue with the athletes, past and present, I am very concerned with how those institutions will actually go about sharing revenue. That’s a result of how power is distributed between administrators, coaches, and athletes.

Many would argue the power balance has shifted towards the athletes in the recent past, mostly with the creation of the transfer portal and, to a lesser extent, with NIL. I agree with that argument, but I remain unconvinced that this shift is as drastic as it has been made out to be. The shift feels drastic because power has been reserved for administrators and coaches since the NCAA was created so any change to that dynamic was bound to feel drastic. An example of this is how people have responded to the relaxation of transfer rules and restrictions, as well as the transfer portal.

In part two, I’ll talk more about power, history, and loyalty and get into how those factors are all contributing to short-term business decisions that I think suggest what the future will look like.

Thank you for reading. I know this is a lot and I don’t expect anyone to be with me on all of it. I don’t assume that the future will be like I imagine it but I can’t get this possible future out of my head. I welcome your thoughts and feedback in the comments. What happens in college sports will end up having impacts on how we all coach and I’m curious to hear from you how you think it will impact your work.

Thoughts on the House Settlement and the Future of College Athletics (part 2)

It’s not my intent to explain the ins and outs of the settlement, I’m doing a bit of speculating and complaining from my specific perspective as a former NCAA Power 4 Olympic sport staff member. If you’d like a bit of an introduction to the House Settlement,