Wooden, Success, and Me

...plus a smidge of Zen

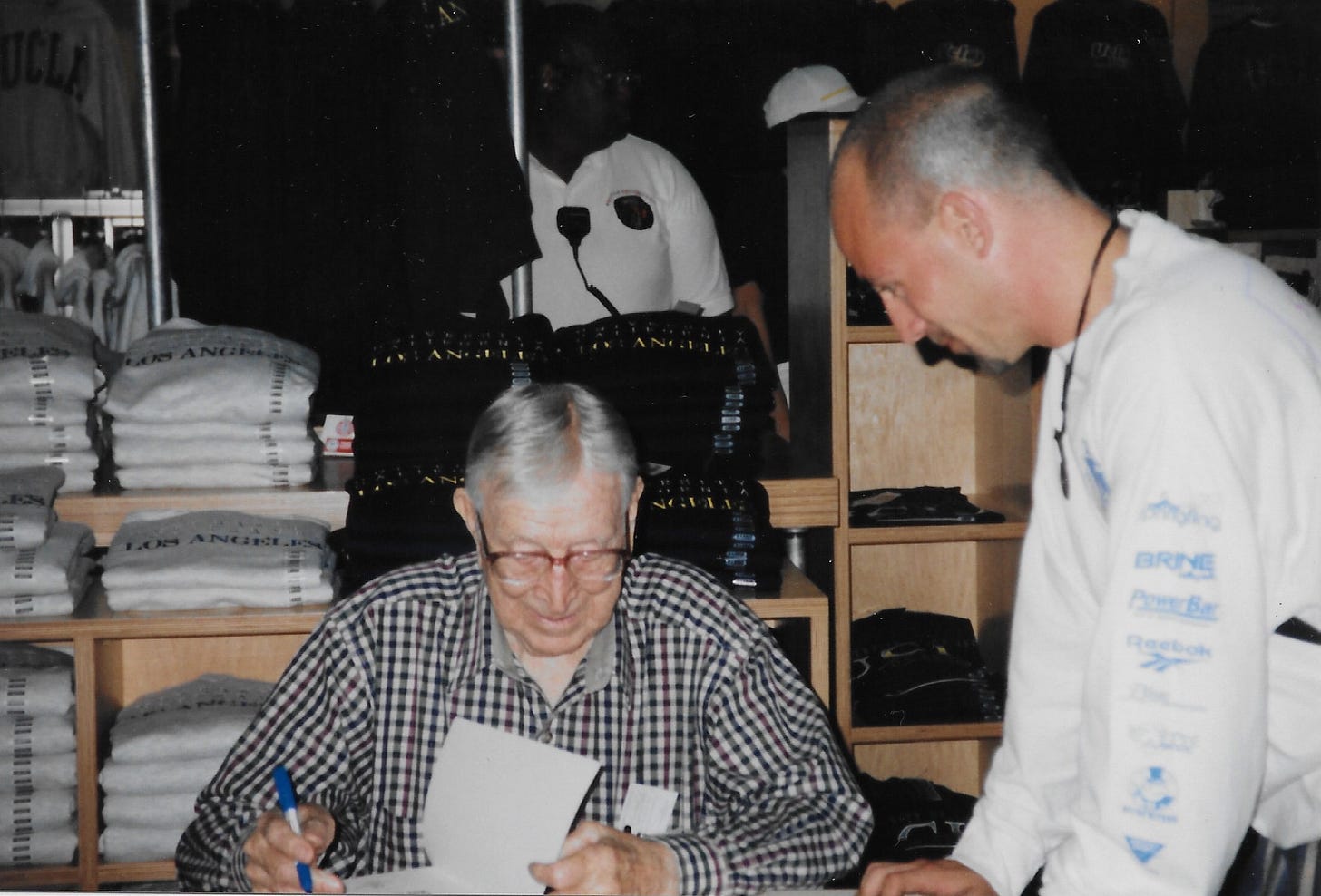

Like many coaches, I was fascinated by John Wooden’s accomplishments and philosophy early in my development. While I have since been exposed to the ideas of many other coaches, Wooden’s definition of success has always stuck with me. I’m often reminded of his definition when I notice people equating success with winning or with perfection.

Success is peace of mind that is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you did your best to become the best you are capable of becoming.

Let’s get it straight, I’m not saying that equating success and winning is wrong or bad. Nor am I saying that Wooden’s definition should replace Webster’s (notice their obsolete definition though). I’m writing to remind us (especially me) that each is a definition and not the definition. We are each free to decide if and when we want to apply each; I want to increase awareness around the consequences of those decisions, not dictate that there is a right choice.

Let’s start with the process/outcome dichotomy. Coaches are constantly faced with choices about being process-oriented or outcome-oriented and they regularly remind athletes of those orientations. Wooden’s version of success appears to be an example of process-oriented mindset but his words hide a goal, becoming “the best you are capable of becoming”. In sport, there are always outcomes that our processes are working towards. But, for him, the outcome was a state of mind, a choice about how you should treat yourself when looking back on the work you put in. So, there’s not really a dichotomy, there is just the intertwining of process and outcome. To me, the apparent choice between process orientation and outcome orientation is actually a reminder to be patient as we go through the struggles of learning, improving, and competing. I think that Wooden was saying that we don’t have to walk out of practice every day feeling that we actually got 1% better, we can measure ourselves by the work that we put in towards improving, confident that, if we keep working like that, we will get better.

Next, let’s look at a concept that is less well-known among coaches, non-attachment. I recently read a Zen teaching, “Everything breaks. Attachment is our unwillingness to face that reality.” To translate to coach-speak, eventually we all lose and our attachment is our belief that there’s always something we could have done to avoid our losses. It’s not that I refuse to accept losses, it’s that I believe that I could have won if only I had executed better. There’s no room for the opponent to be better than me, there’s no room for chance. I turn Wooden’s words against themselves. There is no self-satisfaction because I will never believe that I did my best unless I win. And then, even when I win, I can always find gaps between what I did and my best. This is perfectionism and perfectionism is attachment, the unwillingness to face the reality that we can’t be perfect. Wooden’s peace of mind is a “direct result of self-satisfaction”, not the direct result of perfection. He’s inviting us to be satisfied with the work, even when it’s not perfect. He’s inviting us to let go of perfection as the best measure of success, even though it may be a goal. What allows us to let go of perfection as an expectation is a willingness to accept that things will break far more often than they will be perfect. If we keep perfection as an expectation, it will ultimately be us that breaks. I can wait until we break and try to glue us back together with comforting words or images of the phoenix rising from its ashes.

Instead, I choose to let go of the outcome once we’ve controlled what we can control. I’m going to do everything I can to give my teams the best chance to win BUT I’m also going to recognize that all I can do is give my teams chances to win. If I/we don’t win, I can always find things that I could have done differently but I rob myself of the self-satisfaction that Wooden wrote about.

I can feel the protests. Not just from you but from me. The protests use words like accountability and tolerance. I can hear the cliché, “if you’re not coaching it, you’re condoning it.” I wonder how I, as someone who works with high performance athletes, can encourage letting go. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic movement wrote “the struggle is noble!” Sometimes I have to recognize my attachment to winning and allow myself to let go of it, however briefly. If I don’t, I negate the nobility of our collective struggles in practice and competition. Those struggles have value and meaning, regardless of winning and losing. I’m going to validate those struggles, win or lose, then get back to work on becoming the best that I/we can become.

If I am relentless about something in my coaching, it is not being the best, but being my best. I am going to be curious about how much I can get out of myself without demanding that what I get out has to be better than everyone else. If I can be my best, then let’s find out how that stacks up against others. I can chase winning and perfection as possible measures of success. I choose to do that by chasing my best, recognizing that, when I am at my best, I give myself the best chance of winning. And then I let go.