“Are We Getting Better?” (part 1)

First, get better at asking questions

This post is an elaboration on something I wrote for VolleyStation Pro users in the US as part of my job at VolleyStation. I thought the messages at the heart of it were worth sharing for non-performance analyst-type people too.

With 1/3 of the women’s NCAA indoor volleyball season completed, many teams are asking themselves some big questions and many of those questions fall under the umbrella of “are we getting better?” While it is important to ask questions like this, just asking the big question is far from enough. To make real, tangible progress on the big questions, you need to get better at asking questions.

Perhaps the most important question to ask (after your first big question) is “do I want my big question to be about learning or about performance?” This question is important because it shapes how you’ll explore your big question. If you’re interested in learning, you’re going to pay much more attention to processes and perceptions. If you’re interested in performance, you’re going to pay more attention to opportunities and outcomes. If you think of the season as a journey to some arbitrary destination, assessing learning is studying things like how the speed of travel varied over the course of the trip or if that speed increased from early in the journey to later on. Assessing performance is studying things like how close you came to your destination or how long the trip took.

Performance analysis is better equipped to answer questions about performance (it’s right there in the name) because those questions are easier to frame in quantitative ways. Questions of learning, while important to consider, are much more difficult to narrow down and collect data on, particularly in the realm of competitive sports because those sports are much more concerned with outcomes, like winning and losing. As a result, what follows is focused on questions of performance.

Asking big questions is interesting and important. But it’s also a lot more work than you think. It takes a lot of work because when questions are big they’re hard to clearly define. And when questions are hard to define they’re hard to answer. One way people try to get around the “hard to define” thing is to look for some objective way of measuring improvement. But big questions don’t have objective answers. While it is possible to look around at how are others are answering their own big questions, you have to recognize that, when you get down to defining things, others aren’t really answering the same question you’re trying to answer.

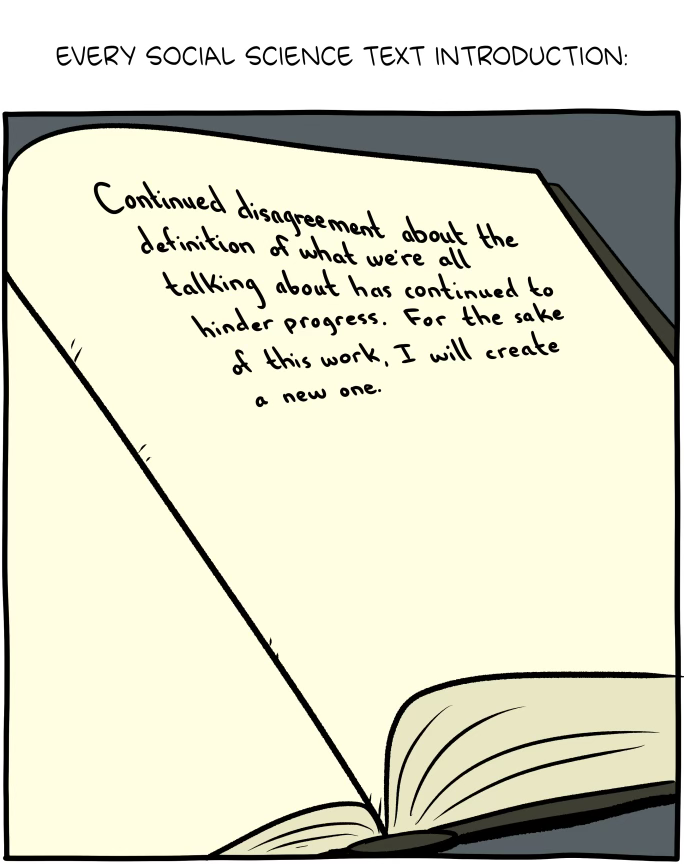

While the comic above appears to poke fun at my point, it actually highlights why having your own questions and definitions is so important. Academic researchers are typically trying to generalize their findings. If they’re successful in their research, they can reach broad conclusions that hold up across many settings. But performance analysts aren’t academic researchers because they’re only trying to understand one very specific setting and it doesn’t matter if their conclusions hold up anywhere else, as long as they accurately explain the setting they’re actually in. Rather than looking outwards to find objective, generic solutions to their big questions, performance analysts and coaches should look inwards, focusing on what their teams are doing and what has helped or is helping them maximize their progress.

When looking inward for answers to your big questions, start by narrowing the scope of those questions. Instead of asking one really big question like “are we getting better?”, ask several questions about different aspects of the game that, taken together, give you a better understanding of the larger question. These questions are still too big, but they get you moving in the right direction. The next layer of questions could be things like “is the offense improving?” and “is the defense improving?” Then you can ask more specific questions like, in volleyball, “is first ball offense improving?” and “is transition offense improving?” While these questions still need further narrowing, it’s important to make something clear about the kinds of questions you ask as you continue getting more specific. As the questions become more and more specific, they should reflect what you value about how your team plays or how teams can win in your area or conference.

When teams are more physically developed or more powerful, first ball offense becomes more important so many pro and international teams care a lot about improving their first ball offense. If you value first ball offense more than transition offense, you should ask if aspects of your first ball offense are improving. When teams aren’t as powerful or as big, scoring in first ball can be less of a deciding factor so transition scoring gains importance. If you value first ball and transition offense nearly equally, then you should devote time to studying the team’s progress in both areas.

As you begin to focus on specific areas that matter more than others, you still need to get your questions specific enough that they can be measured in meaningful ways. For example, “is our transition improving?” is a reasonable question to ask, but complex enough to still not have a straightforward answer. Transition is composed of several factors, each of which is worth exploring. You could ask more-specific questions like, “is our transition kill percentage increasing?” and “are our create and convert percentages increasing?”

But, before I get into actually measuring performance, there’s one more quick tangent to go off on. Notice that, in the paragraph above, I asked if a couple of percentages were increasing. It’s important I mention that “getting better” is not as simple as what the cryptocurrency people like to preach: “number go up”. If only it were that easy. You need to keep in mind how other factors might be impacting what it means to get better. For instance, what if you’re interested in using your transition kill percentage as a way of measuring if your transition offense is improving? What if that kill percentage remained consistent over a certain period but the number of transition attack errors decreased during that same time? You could say the offense has not improved because kill percentage remained constant or you could say the offense has improved because, even though the team didn’t score more points, it also forced opponents to earn more of their own points. It’s a subtle difference and one could reasonably argue either side. Ultimately, it becomes a matter of how you want to define “improvement” within the narrow scope you choose to study.

You can run yourself ragged trying to figure out all the metrics that contribute to team improvement, even within a limited scope. So part of asking better questions is setting limits on what’s worth your time and focus. The other part of asking better questions is setting standards for what progress will look like before analyzing the data. I’ll address those in part 2 of this series.

If you’re interested in digging into the topic of how to measure performance in ways specific to your program, I’ll be leading a small group discussion about that at the AVCA convention in December.

If you’d like to see the comic above, click here.