“Are We Getting Better?” (part 2)

Asking better questions is no guarantee of getting better answers

This post is an elaboration on something I wrote for VolleyStation Pro users in the US as part of my job at VolleyStation. I thought the messages at the heart of it were worth sharing for non-performance analyst-type people too.

In part 1 of this series, I described the importance of narrowing down big questions in an effort to make them manageable and measurable. I ended telling you that questions weren’t the only thing you need to limit. Trying to answer too many specific questions is no better than trying to answer only a few overly broad questions. I also told you that it’s important to decide what improvement looks like before analyzing your data. If you don’t decide what you’re aiming at, it’s hard to know if you’ve hit anything worth hitting. (And if you wait until after you hit something and then draw a target around it, that’s its own problem.) After those two issues are handled, the last hurdle to be cleared, the last question to answer, is which data you should analyze to answer your big questions about getting better.

In part 1, I told you that asking one big, broad question was bad and that breaking that question up into multiple, more specific questions was better. Now, I’m opening part 2 by saying that a bunch of specific questions are also bad. What’s a coach to do? Decide what enough is. Just because you can measure and study something doesn’t mean you should. To paraphrase a line from the 1992 movie, “A League of Their Own”, you should be able to see enough to know when you’ve seen too much. While you can keep piling more metrics and studies onto your to-do list, many of them are going to point in the same direction. You can get the same sense of what’s happening by prioritizing the questions you decide are more important to you and drawing the line somewhere between the metrics that you believe are really important and the ones you believe are only somewhat important.

As I’ve written about previously (towards the second half), there is a line between what you could do and what you should do. The factor separating the really important from the somewhat important from the less important is what impacts your decision making. The things you should do, the things that are really important and worth pursuing, are the ones that you believe can lead to noticeable differences in your chances to win.

Much has been made of marginal gains in sports and I’m not going to make a case that there’s nothing to be gained by looking at details, but I am going to say that marginal gains make more of a difference when your sport is timed rather than scored. It’s really hard to do enough of the marginal things in the span of a single point to get them to add up to actually scoring a whole point. The things that should change your mind are the things that are more directly tied to scoring than marginally connected. Those are what you should consider to be big rocks. If you spend your time figuring out if you’re getting better at the small rocks, you might find you’re improving those but they aren’t having any effects on the win column.

Keep the main things (those that have larger impact on winning) the main things by limiting your questions to those that are more proximal to how you believe scoring and winning happen. Make choices about what you’re going to prioritize and what you’re not. Acknowledge you will always have some doubt about how you ordered your priorities but make your choices anyways. The choices about what you’re going to prioritize have to be made so you can move forward with what you’re going to study and how.

The next step is to decide how you’re going to define “improvement”. Since I’m focusing on performance, the answers about what improvement looks like revolve around differences in performances and how large those differences are expected to be. Whatever you choose to compare present performance to is a standard. You are measuring how the difference between current performances and that standard changes over time. Improvement is about how much that difference changes and it’s up to you to decide if that change is adequate or appropriate or helpful. What I’m saying is that, contrary to popular belief, standards are actually quite subjective and arbitrary. But that doesn’t make them bad. It’s just that “standard” can mean something different than you might have thought.

In truth, “standard” means what you thought, an “agreed level of quality” but I argue the definition you should be using, especially when asking questions about improving, is a “thing used as a measure”. The point of this kind of standard isn’t to reach it or be better than it. The purpose of the standard is just to serve as a fixed point you can use for “comparative evaluations”. There doesn’t have to be anything special about what you compare current performance to. With that understanding, decide what you want to use as your standard.

Standards can be put into three different categories: past, present, and future. Comparing present performance relative to the past can mean looking at differences between the beginning of your current season and the present. But differences relative to the past can also be between performances at the same point last season and current performances. Present comparisons can mean looking at differences between current performances and current performances of teams similar to yours during the same period. Future comparisons can mean looking at differences between current performances and where performances are expected to be by some arbitrary point in the future, like the end of the month or the end of conference play. (To me, future comparisons are great opportunities to connect present performances to end-of-season, team banquet-type goals.)

Regardless of which category of standard you choose, the challenge that remains is where to set the standard for comparison. If you choose a standard that is greatly different than present performances, it’s easy to lose any sense of scale. Getting better is an incremental process and it is difficult to measure small incremental changes when what you’re measuring against is so far away. It’s better to choose a standard that is somewhat closer to current performances so smaller changes become more apparent. I’m suggesting that, even though it is tempting to use national champions and All-Americans as standards, it’s more useful for most coaches to choose standards that represent modest gains or separations. You can always choose new standards if your initial choices end up being eclipsed too quickly for your taste.

All of this talk of standards assumes that they are something to be reached, but you reach goals, not standards. Remember the definition above, standards are just a tool for comparison. Further, the word “better” is a comparative word, getting better is relative to something else. Standards and “getting better” are not goals, they are just measuring changes and differences. The last piece, then, is deciding how much change you need to see between current performances and your chosen standard before you are willing to call it “better”. Getting better is a process, but being better is a goal. If you want to say you are now better, you need to decide on a threshold. That threshold becomes your goal, the point at which you can answer “are we getting better?” affirmatively.

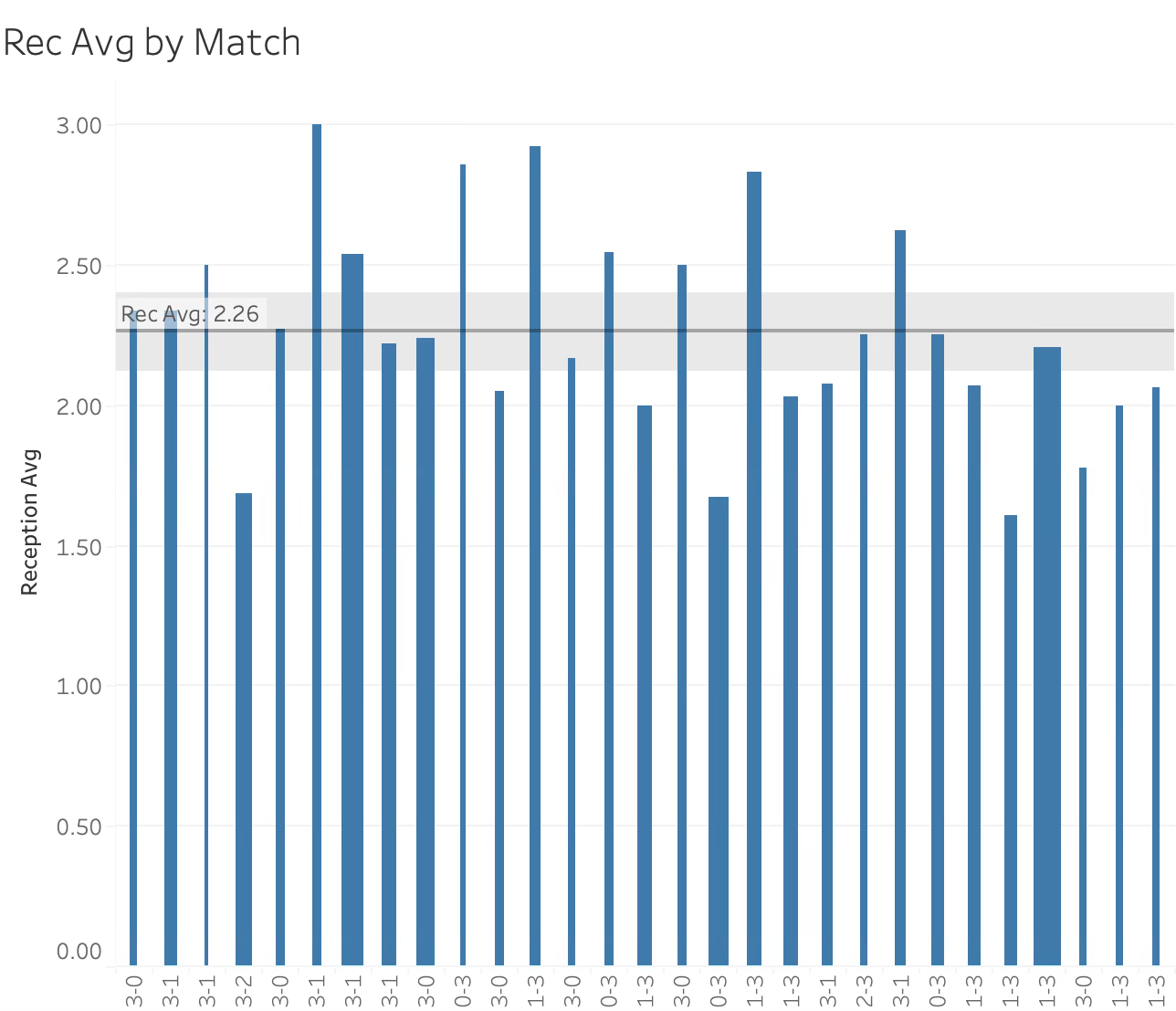

How much do the numbers you currently see need to change for you to judge them as signaling “better”? Don’t settle for the smallest of changes, but also don’t place the bar for what counts as “better” so high as to be perpetually out of reach. (That’s a part of my reasoning for choosing standards that aren’t at the extremes of performance.) The graph above shows the danger of looking for the any change, performance is inherently too variable to consider any change to be associated with a new state of performance. Further, if you are measuring multiple metrics (which I recommend), the variability of performance means you’re likely to see mixed results, with some metrics moving in one direction while other metrics move in a different direction, each with their own magnitude.

Asking big questions about improvement isn’t anywhere near as simple as it seems, at least if you want to do it well. You need to narrow down your big questions into smaller, more-focused questions that reflect what you care most about and how winning happens in the games you play. You need to choose metrics that reflect those values and realities and those metrics need to be measured in some consistent, reliable way. You need to accept the limits of what you should study and leave less important questions for another day. You need to choose standards against which you will compare your current performances. You need to define what “better” will look like in your chosen metrics. And after all that, You need to let go.

Like with the coaching you do, all your preparations are no guarantee of success. In the end, you may end up with metrics telling conflicting stories about the state of performance. And that doesn’t mean you’ve done something wrong or that you’ve wasted your time. Improving is hard and it’s inconsistent. So it measuring improvement.

(If you’re interested in digging into the topic of how to measure performance in ways tailored to your program, I’ll be leading a small group discussion about that at the AVCA convention in December.)

Here’s the line from “A League of Their Own”: