Reading is Fundamental…for Coaches (part 1)

What would you do if learning in sports wasn’t like learning in a classroom?

Many of the concepts about learning I present here are framed by the work of Barbara Rogoff and others in the psychological field of situated learning. In particular, I rely heavily on a book chapter Rogoff wrote in 1997 called “Evaluating Development in the Process of Participation: Theory, Methods, and Practice Building on Each Other”1. All quotations below are from this text.

The clip below comes from the 1992 film “A Few Good Men”. I sometimes think of this scene when I think of what many people would perceive as “learning” and what you might call “reading”.

Many coaches, across various sports and perhaps using slightly different language, have emphasized the importance of “reading” the game as a skill for players. Coaches have called it “game IQ”, “game sense”, or “awareness”, among other things. They’re usually trying to get players to make decisions dynamically or intuitively, based on what they see unfolding during play, rather than just applying formulaic steps of executing skills, regardless of how well those steps fit into the current situation. Teaching players to “read” is a great goal to have and players who can read successfully tend to be ahead of their peers who cannot.

But there’s a larger question to be answered. Are you reading as a coach? In other words, are your teaching methods just formulaic steps of executing coaching moves, regardless of how well those steps fit into the current situation? Too often coaches use static tools in their efforts to teach players to be dynamic and flexible. Using teaching tools that don’t align with learning goals leads to frustration in mentors and learners alike. The psychologist and researcher Barbara Rogoff describes aligning your tools this way: “With an emphasis on participation, the emphasis for the…questions shifts from trying to understand the acquisition of capacities or skills or mental objects to understanding the processes of participation.” If you want players to read the game effectively, then you should read how they function in their games so you can support their efforts.

What does it mean to read how they participate? It means expanding your understanding of what learning is. Many coaches approach knowledge as a thing that can be gained, possessed, and passed on to others. While this view of knowledge as a commodity is far from wrong, the view can limit the ways in which coaches work with athletes. It leads to coaches believing that teaching requires transmitting knowledge to players, which means the players are responsible for acquiring that knowledge. That might work for memorizing pieces of information but, when it comes to the kind of teaching and learning required in sports, here’s the thing…

Talking isn’t teaching and listening isn’t learning

Rather than assuming learning is a process of acquiring information, what if you thought of it as, to paraphrase Rogoff, “transforming participation in activities”. In this view, learning isn’t listening, it’s doing. That means teaching becomes giving athletes things to do that allow them to transform how they interact within activities. Before I can get into what you can do coach this “transformation”, I need to talk more about what “participation” is.

Viewing learning as changing behaviors in changing situations means you, as the coach, have to look at more than just a “skill” in isolation. Sports, especially team sports, aren’t just neat, sequential executions of skills. Sports are composed of interactions between competitors, teammates, objects, and the environment. Reading means acknowledging that performing a skill is not participation and what you might call skills “cannot be isolated [from an activity], and none is primary except with regard to being the current focus of attention.” In competition, skills are performed in response to and/or in conjunction with other parts of the activity in which the performer is engaged. Teammates coordinate with each other to determine who will make a play while also considering how their opponent is defending against them.

And yet, contrary to Rogoff’s observation about isolation, coaches construct practice situations that separate skills from the activity they are part of. When coaches view skills in isolation, the goal of execution becomes to make it look like it does in the coach’s head. “In transmission and acquisition views, the assumption is that in order to evaluate learning the individual must be isolated and a standard procedure applied to ‘measure’ competence as pieces of knowledge that have been obtained. Because learning is considered to be contained in the individual, in order to figure out if somebody has learned something one has to isolate them from any other sources of assistance or influence.” But this view, while much simpler and easier to both understand and control, does not reflect the reality you coach in.

While isolating skills does tell accurate stories about the reality coaches work in, those stories are such tiny pieces of the whole that they become nearly meaningless. But, because they can be more easily understood and explained, coaches use those tiny stories as proxies for the reality they seek to coach. It is the proverbial “missing the forest for the trees”. In order to understand a skill on its own, the coach ends up having to ignore the conditions that led to the execution of the skill itself. The problem is that those conditions affect how players understand what is happening and what their possible choices are. Coaches who seek to read should seek to include more of the context in which skill execution happens.

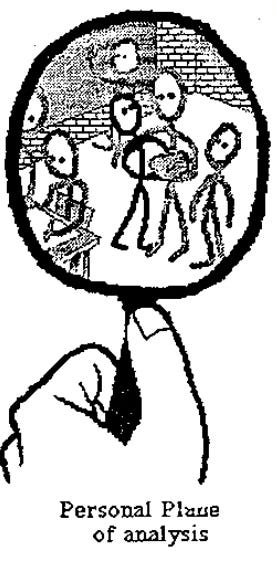

Part of reading as a coach, then, is allowing the skill to exist in its fullness within the activity and then focusing on the skill as it happens in full flow. Rogoff explains the rationale clearly: “In an analysis focusing on individual processes, the individual’s contributions are in focus and those of the other people are blurred, but one could not interpret what the individual was doing without understanding how it fits with what is going on around.” She is telling coaches that isolating skills misses the point of what those skills are supposed to do. Skills are what players do in order to score or prevent an opponent from scoring. Skills aren’t something players do for the sake of performing skills, but that’s what happens when you coach them in isolation. She is telling you to look at more than just the skill.

The drawing above shows what Rogoff is describing: the individual in focus, others blurred but still visible. It demonstrates that it makes more sense to think of interactions and ways of participating than to think of skills. When coaches view skills as part of a larger activity, they are better able to see the interactions that lead to the actions they’re used to focusing on. Coaches may argue they already observe skills within the context of the game, like when they coach during competition. But that’s still picking out tiny bits of an activity and pretending those bits accurately represent the full activity. To get used to viewing whole activities instead of skills, ask yourself questions that focus on participation instead of questions that focus on execution.

While I have much more to say about participation, I want to stop here and give you a chance to try this way of viewing the sport you coach, the players playing that sport, and, you, the coach. When you try to keep the whole activity in view and understand how all the participants (including you) interact, how does your perspective change? What happens when you try to stop viewing tiny, easy-to-explain, skill-sized slices of the game? How are you making sense of the role you play as a coach when you start reading?

In part two, I’ll give you more details about what coaching for “transforming participation” looks like.

Reading is Fundamental…for Coaches (part 2)

Many of the concepts about learning I present here are framed by the work of Barbara Rogoff and others in the psychological field of situated learning. In particular, I rely heavily on a book chapter Rogoff wrote in 1997 called “Evaluating Development in the Process of Participation: Theory, Methods, and Practice Building on Each Other”

Rogoff, B. (1997). Evaluating development in the process of participation: Theory, methods, and practice building on each other. In E. Amsel & K. A. Renninger (Eds.), Change and Development: Issues of Theory, Method, and Application (pp. 265–285). Psychology Press.