Reading is Fundamental…for Coaches (part 2)

Many of the concepts about learning I present here are framed by the work of Barbara Rogoff and others in the psychological field of situated learning. In particular, I rely heavily on a book chapter Rogoff wrote in 1997 called “Evaluating Development in the Process of Participation: Theory, Methods, and Practice Building on Each Other”1. All quotations below are from this text.

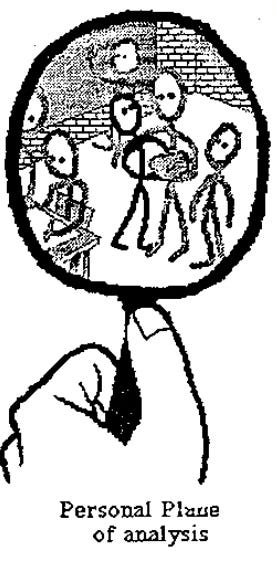

In part one of this series, I left off with the drawing above, showing Barbara Rogoff’s description of participation and what it means to observe participation instead of isolated actions. When observing participation, an individual and their actions might be in focus, but the observer keeps the full activity in view, even if the rest is a bit blurry. It demonstrates that it makes more sense to think of interactions and ways of participating than to think of skills. When coaches view skills as part of a larger activity, they are better able to see the interactions that lead to the actions they’re used to focusing on. Coaches may argue they already observe skills within the context of the game, like when they coach during competition. But that’s still picking out tiny bits of an activity and pretending those bits accurately represent the full activity. To get used to viewing whole activities instead of skills, ask yourself questions that focus on participation instead of questions that focus on execution.

Allow me to quote Rogoff at length to set up what I’m pointing towards.

Inspiration for the evaluation of learning from the perspective of a transformation of participation perspective derives from observations of classroom evaluation of children’s learning in an innovative public elementary school in which children are rarely given tests but teachers have rich information on children’s development and learning of the curriculum (Bartlett, Goodman Turkanis, & Rogoff, in preparation). The evaluation derives from collaboration with the children and observation of the roles that the children begin to carry out in the learning activities.

Teachers evaluate learning to write, for example, in terms of whether children are at the point of needing assistance in becoming involved at all in writing, or write with interest of their own. Do they write only in response to requests to do so or to initiate communication through writing? Is their writing embedded in a very limited range of activities or is it broadly used? As they write, do they consider the understanding that a reader will make of their written communication, or are they tied to writing for themselves alone? As fledgling writers, do they take responsibility for editing their work for its meaning and its ease of being read, or is this a role that needs close support from another person?

First, notice what Rogoff doesn’t talk about. No one is asking questions about how the students hold their pens or where their fingers are on the keyboard. There are no questions about grammar or punctuation. To be clear, Rogoff is describing an elementary school, so how the students perform the skills of writing is still developing. And yet, the teachers aren’t concerned with developing competent sentence structure-ers or outstanding calligraphers nearly as much as they are concerned with nurturing writers.

But, notice there are questions that involve writing clearly and neatly. The “skills” of writing legibly and cogently aren’t treated as ends in themselves. They are things a writer learns to do in service of the activity of writing. Instead of focusing on writing “skills”, teachers observe if and how fledgling writers seek to communicate their ideas to others. Teachers observe what the writers choose to write about and what kinds of help, if any, the writers need or seek out. This is what it means to focus on participation. The physical skills of writing matter only insofar as they allow the students to be writers.

Like teachers who seek to nurture writers, coaches focused on transformation of participation seek to nurture competitors and teammates. Such coaches observe play and ask questions like…How did the ball’s flight affect the player’s efforts? How did the positioning of their teammates and their opponents affect the player’s understanding of the situation? How did they adjust their actions in light of what they saw? These questions respect that players are immersed in an activity and that there are opponents and teammates that affect how situations are interpreted and responded to. Respecting what the activity is about and observing from this point of respect are the roots of reading as a coach.

So what’s a coach to do with what they observe? How are they supposed to nurture competition and collaboration? Rogoff writes that “[t]he central questions raised in the transformation of participation view have to do with how people’s participation changes as an activity develops.” Once you begin to view participation instead of skills, you’ll need to do two things to nurture transformation.

The first part of reading is observing how players understand and interact with the activities they participate in. One layer of observation is to see how players understand the state of the game they are playing. How do they understand what the opponent is trying to do to them and what they and their teammates are trying to do to their opponent? What options do they think they and their teammates have to absorb the opponent’s pressure and to create pressure of their own? Another layer of observation is to see how players view different roles within competition. Are there actions they alone can take? Are there actions they can collaborate with a teammate to create that they cannot create alone? Who do they see themselves as being within the structure of the team? How do they believe they can contribute to winning? How do they believe they can they contribute to improving?

The second part of reading is observing how players change their understanding and their participation. Competition (and practice, for that matter) is always changing. How do players’ behaviors and beliefs change as the activity changes around them? What do they do differently as the score changes? What do they do differently when the quality of the opponent changes? How do they change when the teammates they are surrounded by change from game to game or season to season? Do they change their beliefs or their roles when they are with their teammates, but are outside of practice or competition? Perhaps most importantly, how does their participation change as their abilities change?

The seeds of the coaching you will do are all in those observations about participation and how it changes. To go back to what I said at the beginning of this, remember that talking isn’t teaching so you aren’t going to just tell players what to do. You’re going to help them shape their understanding of their activities. Consider what Rogoff’s writing teachers might ask students. “I’m not sure what this sentence means. Please tell me more about the idea you’re trying to share. Is there another way you could say it that might help me understand?” Consider what someone who wants to nurture competitiveness might say to a player during a game. “What might your opponent have been trying to do you there? What if their intention had been x instead of y? How would you respond differently?” Consider what someone who wants to support growth might say to a player during practice. “Remember what you would do in this situation last year when you were coming off the bench? What could you try in that situation this year if you were starting?”

Reading, whether as a player or as a coach, is about observing and responding to an entire activity rather than isolating and commenting on a single action. Reading is about remembering the larger picture that gives individual skills their meaning. If you want players to read the game, then you need to read what and how players are reading. You need to read how they are participating and what they think their participation means. That’s how you lead them to changing their understanding, which is the key to enabling changes in their participation. That’s not just talking, that’s teaching. And that’s not just listening, that’s learning.

Rogoff, B. (1997). Evaluating development in the process of participation: Theory, methods, and practice building on each other. In E. Amsel & K. A. Renninger (Eds.), Change and Development: Issues of Theory, Method, and Application (pp. 265–285). Psychology Press.