Short Circuiting Human Development

A Lesson in Learning from…Engineers?

I recently wrote about double loop learning so let’s keep the theme of learning loops going by looking at…circuits! It’s almost certainly not immediately apparent how basic electrical engineering relates to human development. But, trust me, how electricity works1 can help you understand an important aspect of learning. Don’t worry, this will only involve structures and not any math.

Circuits, at their simplest, facilitate the flow of electricity and there are two basic ways to connect circuit components, in series and in parallel. What’s interesting is how those two connection methods facilitate flow. That’s where the similarities to how learning can be viewed emerge.

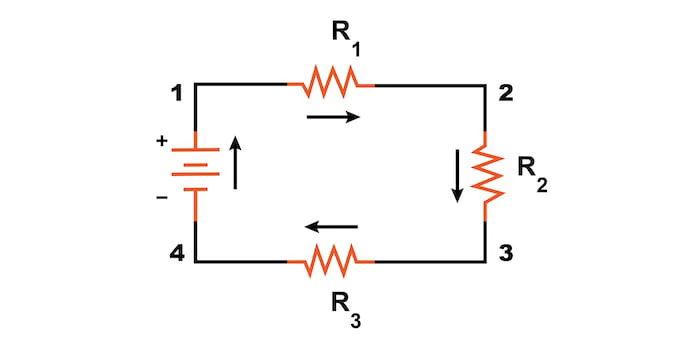

A series circuit is one in which “the components are connected end-to-end in a line”. In the diagram above, current flows counterclockwise and flows through the resistors in order, R₁-R₃. This is the only way for current to flow through the circuit. Further, if there’s a break anywhere in the circuit, the current is disrupted. It’s like when you have an old string of Christmas lights and one of them goes out, causing the whole string to go out.

In learning, a series circuit is like learning the “fundamentals” before other concepts. If players aren’t executing the fundamentals, then there’s no point in moving on. The lack of fundamentals disrupts the learning “current”. Viewing learning as a series circuit is widely accepted. But learning in series isn’t the only way to view learning. Just like good strings of Christmas lights and light switches around the world, there are other ways to keep the current flowing.

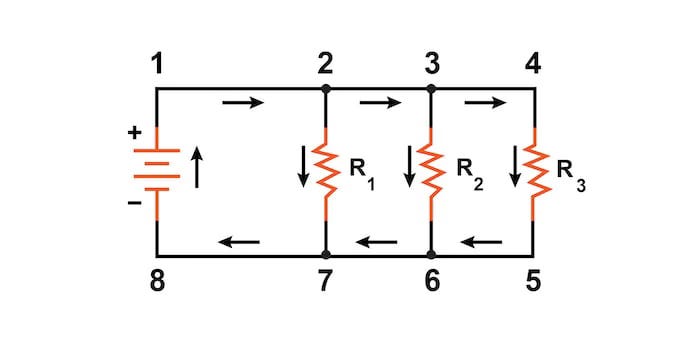

A parallel circuit isn’t as easily defined in non-technical terms but, at the risk of oversimplifying, call it a circuit in which all components are connected and current can flow through all of them, but there are many paths for the current to flow through. In the circuit diagrammed above, current can still pass through all three resistors, but it doesn’t have to. It can pass through any combination of the three. (Current can’t flow through them in any order, but that’s not a concern for the discussion here.) If you have a room with multiple light switches, the switches usually all run through one parallel circuit, allowing you to turn on or off any combination of switches so you can have the ceiling fan running while the lights on the fan remain off.

In learning, a parallel circuit expands possibilities. While there are still “fundamentals” to be learned, they don’t have to be learned before other things. They can be learned simultaneously with other concepts. And, if they’re not being practiced at a particular time, other concepts aren’t kept waiting. Learning in parallel is uncommon, it isn’t something people are regularly exposed to. There are two ideas you need to consider in order for learning in parallel to make more sense.

First, coaches need to consider that learning “fundamentals” first may actually be limiting. There’s the old cliché in coaching that you shouldn’t attempt tactically what you can’t do technically, which suggests players must first learn the fundamental technical pieces of certain common tactics. But this approach needlessly limits tactics by falling prey to deficit thinking2. It assumes that the envisioned tactics are necessary for success and that the lack of skill is a flaw in the players that must be corrected. But what if learners were given opportunities to figure out what they can do tactically with the skills they already have? That’s a strengths-based way of thinking that facilitates growth by looking for ways to build on what already exists rather than focusing on perceived gaps in abilities. It requires exploring what players and teams can currently do and how to maximize those skills while also exploring ways to grow those same skills over time.

Second, coaches need to consider that fundamental techniques and tactics aren’t what make players great or even above average. Average-but-fundamentally-sound learners are everywhere. But above-average learners separate themselves because of what they can do around the fundamentals not because of the fundamentals. If that’s the case, shouldn’t learners have opportunities to work on things around the fundamentals as much as possible, even if they haven’t mastered the fundamentals? That’s what parallel circuits are meant to do.

But, if I’m honest, I’ve been keeping something from you. Notice I deliberately referred to learning as much as possible, rather than talking about coaching. I let you think I was talking about players. And learning in parallel is important for them too. But, just like Steve Jobs used to do, I buried the lede.

There’s one more thing you need to know. I’ve really been talking about how you learn. While players also benefit when coaches facilitate their learning in parallel, what I really want to make clear is that coaches should be learning in parallel too. You don’t have to focus only on coaching player technique and collecting drills from other coaches.

When experienced coaches are asked what makes them good at their craft, they bring up a wide assortment of characteristics. But they never talk about how many drills they know. There are great coaches who have very different opinions about how skills should be performed. Knowledge of technique isn’t what makes coaches great, just like having rock-solid technique doesn’t make players great.

And yet, coaches almost universally start their careers thinking they need to master techniques and drills. They spend years thinking those are the fundamentals they must master before they can move on to other things that, it turns out, are what actually matter. But, rather than being “fundamental”, techniques and drills are only a couple of tools of the coaching trade. Possessing tools is not the same as knowing how to use them. Less experienced coaches assume there is no difference between possessing and using, so they assume their pursuit of learning can (and should!) be done in series. If you think all you have to do is acquire fundamentals, there’s no need to pursue anything more than that acquisition, then you would do that first and not allow yourself to be distracted by other things.

But that isn’t pursuing learning, that’s pursuing expertise instead. There’s good reason to be wary of pursuing expertise. Coaches are expected to be experts in their sport from day 1. They are expected to show their expertise primarily by always having the right answer. This sets up a series circuit in coach learning in which coaches respond to expectations by spending their early careers making sure they have answers before they start developing other aspects of coaching. This pursuit of expertise, of having the right answers, keeps them from developing other areas of their coaching.

Why is it so important to develop other aspects of your coaching, especially early in your career? Because you’re always coaching far more than skills and technique. Coaches who pursue expertise over pursuing learning assume their values don’t matter and don’t affect the work they do. But your values are impacting what players learn from you so you should coach in a way that reflects that fact. There’s a host of academic research on coaching that shows “…athletes were not merely learning technical and tactical lessons but developing attitudes, values and beliefs.”3 You can and should be paying attention to how your coaching is impacting the formation of those attitudes, values, and beliefs. That means you should be working on how you coach those as well as coaching technical and tactical lessons.

“As well as” is a hallmark of a parallel circuit. Creating a parallel circuit in your development de-emphasizes the focus on expertise and opens possibilities to develop other areas of your coaching. So how do you create a parallel learning circuit for yourself? You use double loop learning to reflect on not just what you’re coaching but why you’re coaching it. Although there is some similarity, this is not the why in the generic “know your why”. This why is much more specific than “why do I coach?”

Double loop learning leads you to ask questions like “why am I coaching this way at this moment?” Answering questions like that helps you define your attitudes, values, and beliefs. When you know those about yourself, they become guides for what attitudes, values, and beliefs players learn from you. They also become guides for how you coach. They become the basis for how you answer the question “what kind of person am I?” in the Logic of Appropriateness framework. Answering that question has far more to do with learning than it does with expertise.

In the end, this is the difference between learning in series and learning in parallel. Series circuits lead to unnecessarily narrowed focus that ultimately limits important learning. When that learning is postponed, it costs coaches years of better, more authentic coaching. But coaches don’t have to postpone learning if they learn in parallel. They can reflect on what their coaching says about their values. They can use what they learn to inform and improve the parts of their coaching they were so concerned about initially. Ironically, widening one’s coaching focus by using a parallel circuit leads to the very expertise that often eludes coaches seeking expertise via series circuits.

All circuit references, including the diagrams, are either direct quotations of or adaptations of ideas in All About Circuits (https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/textbook/direct-current/chpt-5/what-are-series-and-parallel-circuits/)

I understand the academic concept of deficit thinking is tied to oppressed groups and hegemony (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/currents/17387731.0001.110/--what-is-deficit-thinking-an-analysis-of-conceptualizations?rgn=main;view=fulltext) and I don’t want to suggest that it shouldn’t be. I recognize I am appropriating the concept a bit, but I also think young athletes (whom I have spent my career working with) are also oppressed, although to a lesser extent, in that the systems they participate in withhold power from them and that power is used to maintain their sense of inadequacy. Grassroots and college sports are, to a large extent, built on the idea that athletes need coaching in order to amount to anything. Coaching, then, can be seen as an act that continually reinforces the need for more coaching rather than less.

Jones, R. L., Potrac, P., Cushion, C., & Ronglan, L. T. (2010). The Sociology of Sports Coaching. Routledge.