Where Do You Start From?

Hint: It Ain’t From Scratch

Welcome back to the beginning. I’ll be waiting for you to come back to the second half. Don’t worry, it’ll all make sense in a few minutes.

When I was a young science nerd, Carl Sagan was an important personality. He said something on his television show, Cosmos, all those years ago, that is surprisingly applicable to coaching.

How in the…umm…universe does this have anything to do with coaching? You’d have to watch the rest of the episode1, all about atoms and subatomic particles, to get to the other clue about coaching. I’ll save you the trouble and skip to Sagan’s last line.

“…we are made by the atoms in the stars; that our matter and our form are determined by the cosmos of which we are a part.”

- Carl Sagan

Sagan’s apple pie quote takes the idea of making something “from scratch” to an extreme, but the second quote helps make clear what he meant: big things that you can see come into existence because of innumerable little interactions. Anything made “from scratch” is really a product of important antecedents. When you start a new season or a new job, the “matter and form” of those things aren’t built from nothing at the moment you begin. That’s the point coaches need to take away from Sagan: nothing you do truly starts from nothing.

Acknowledging that teams and coaches don’t start from nothing isn’t about checking egos or acknowledging those that preceded you. While the lessons of history are important, they don’t address where you are, right now, in this moment and how things came to be that way. Coaches don’t start from zero. Teams don’t start from nowhere. But if you don’t start from nowhere, then you’re dropped in the middle of somewhere. Figuring out where “somewhere” is impacts where you’re going and, more importantly, how you’re going to get there.

The challenging thing about figuring out where you’re starting is there’s so much confounding information. Unless you’re paying close attention, so much of what you do looks a heck of a lot like what everyone else is doing. As a result, coaches often assume the game is played pretty much the same way everywhere and, therefore, everyone starts in the same place and moves in the same direction towards the same goal. Guess what? It isn’t and you don’t. The history of the game is not your history. The rules are the same, but who and what they are applied to are not.

Not everyone plays the game the same way, even within the same rules. Because not everyone plays for the same reasons or with the same goals. Because everyone plays with different people. That means there isn’t one start line that everyone lines up on. That means everyone does not move towards one designated finish line. Nothing is the same. Not the starting line, not the length of the race, not even the starting time. The finish often isn’t the same either. That’s why figuring out where your somewhere is holds so much importance.

Here’s another trap you fall into when you assume common start and end points: you also assume you can just follow the same path as others you might seek to emulate. If you haven’t realized you aren’t actually on the same path they are, then it won’t make sense when what they did doesn’t work for you. It’s like you’re using a map that describes a different place than the one you’re in. Why would you expect the map to lead you anywhere if it doesn’t describe where you are?

I’d argue that, contrary to how coaching is usually done, deciding where you are is more important than deciding where you want to go. A map can’t know where you are, and there’s no GPS for you to rely on. You have to be able to match where you are to a map that will help you navigate to where you want to go. It can be okay to choose the same end point as others, but not until you understand where you are and where they are. Assessing the difference in locations will allow you to evaluate how your paths will differ instead of blindly expecting to be able to mimic their path, step for step.

Instead of starting with questions about what others are doing or where others are going, you could start with questions about what you have in common with them and what makes you different from them. Questions like the latter help you learn more about where you aren’t. But it’s more important to ask questions like the former, ones that help you figure out where you are. Questions like those are centered on describing the landscape around you, instead of assuming it’s the same landscape everywhere or assuming the landscape doesn’t matter. Ask yourself how the game is played close to where you are instead of how it’s being played by “the best”. Ask yourself how your team fits in with how the game is played near you. Ask yourself how you can differentiate your team from the teams around you instead of expecting your team to play like some team far away from where you are.

If you can see the value in understanding where your team is, I want to challenge you to push the idea even further. Go back to the beginning and read this again, but instead of thinking about a team, think about yourself.

Welcome back to the second half. Time to talk about your journey.

That’s right, there’s more to coaching than just figuring out where the team is. There are actually two maps you should be aware of, two different landscapes that shape the coaching you do. There’s the team’s map and there’s your map. The two maps affect one another but they definitely do not cover the same territory. Your map isn’t the same as the team’s map but it’s just as important. Your journey through your territory matters because it ultimately shapes how you understand the team’s map.

It may be helpful to consider the old sports cliché, “play our game”. Or, to keep with the map/territory/journey metaphor, consider the phrase used regularly by Appalachian Trail thru hikers, “hike your own hike”. Your job is to figure out what your game is, not just accept the game “the best” play. Your job is to figure out what your hike looks, sounds, and feels like, not just walk according to the expectations of others. Your job isn’t to be authentic to some idealized version of a coach, your job is to be authentic to the you that you are and that you want to be.

Just like the team, you don’t start at the same start line as everyone else when you start coaching. You are not a blank slate, even if you’ve never coached before in your life. You begin your coaching career full of experiences, opinions, interests, and ideas. Those things all contribute to the somewhere you start from. Your “somewhere” is the framework into which all the coaching ideas you seek out and are exposed to need to fit (or not fit).

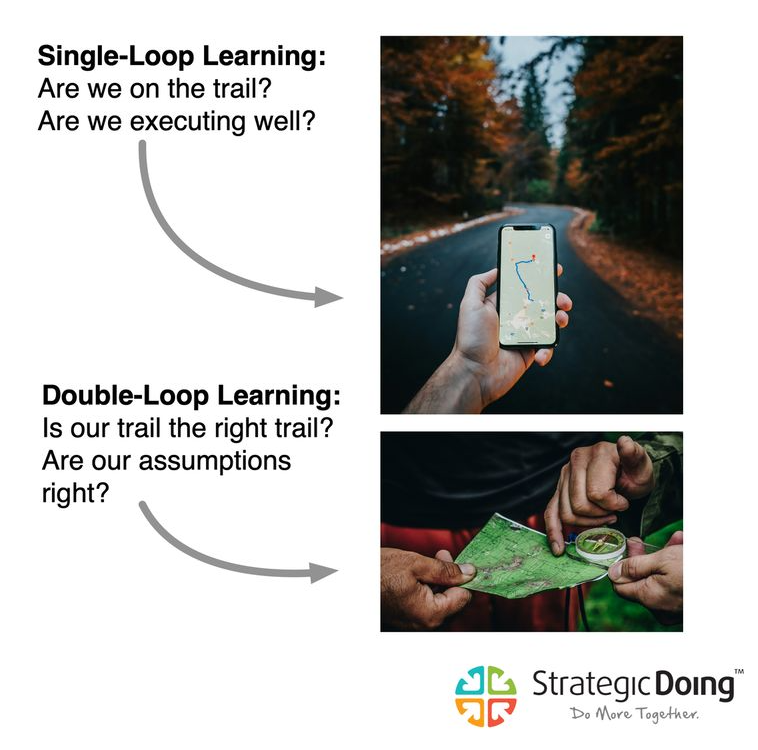

The process of discovering your framework and growing that framework while you’re coaching is what Harvard business theorist Chris Argyris called “double loop learning”. He described single loop learning as being like a thermostat set to 68 degrees. It “learns” what the ambient temperature is and adjusts its systems in accordance of a set of rules. He went on to say that double loop learning is when the thermostat asks why it’s set to 68 degrees instead of some other temperature and if it should change its setting. Double loop learning is when the thermostat asks if there are other ways to achieve the same temperature.

In single loop learning, there’s no investigation of the framework that determines how decisions are made, the only thing investigated are the decisions themselves. In double loop learning, considering the framework becomes part of learning. Double loop learning and developing your framework involve reflecting on what Argyris called espoused theories and theories in use. Your espoused theories are what you say matters to you in your coaching. Your theories in use are the things you actually do in your coaching.

How do you learn what your framework and your theories look like? Figuring these out is done by paying attention to and reflecting on what you believe about learning, teaching, competition, motivation, and connection. These are your espoused theories, the things you say you believe and value. If tackling those big ideas seems intimidating, start with something coaches are more inclined to do: pay attention to the drills and games you use. These reflect your theories in use. Ask yourself reflective questions about your response to the drills and games you use. What is it about them you like or dislike? While you’re using them, when do you feel like you’re doing your best coaching? What is it about them that helps you focus on things you care about?

Coaches don’t commonly ask questions like these of themselves. That’s why they don’t tend to figure out their frameworks until later in their careers: because they occupy themselves with questions that don’t help them reflect. Those questions keep your learning in a single loop. Reflective questions engage the second loop and help you figure out what you value. Knowing your values is how you figure out where you’re starting from as well as where you want to go. The questions you ask yourself should be about what Penn neuroscientist Emily Falk, author of What We Value calls “self-relevance”. The questions should help you discern what are “me things” and what are “not-me things”.

Coaches don’t typically consider these topics because no one ever told them they were important to consider. It’s always been assumed they could just go “do” coaching and, eventually, that would lead to “being” a coach. While that’s true, you can do better by reflecting on what makes you be better first. Get out of single loop learning and into double loop learning to get better at being the coach you should be. You’ll find being that coach will inevitably lead to doing better coaching.

Being the coach you should be begins when you stop assuming you start where others start, when you stop assuming you need to finish where others finish, and stop assuming you need to follow the same path as others. That prepares you to do the work of double loop learning that shifts your focus from doing coaching to being a coach. These processes help you figure out who you are, where you are, what’s worth doing, and how you should go about doing it.

Cosmos, episode 9, “The Lives of the Stars”, 11/23/1980 (https://www.organism.earth/library/document/cosmos-9)