How to Make Your Practices More Efficient (part 1)

How folk pedagogies get in the way

This is an adaptation of my 2025 AVCA webinar. You can watch the video here.

How do you make your practices more efficient? It’s easy. End your drills/games/sessions on time, regardless of whether the goals have been achieved. Or set goals such that they can always be met. Doing those things will ensure your efficiency.

And yet, that succinct answer rings hollow. Why does my answer feel so unsatisfactory? Because you’ve been taught being “good” means meeting high expectations consistently. You’ve been taught it’s not acceptable to be time-efficient but not results-efficient. And yet, your personal experience tells you that being efficient in both time and results simultaneously rarely happens. Since they rarely happen together, then learning to be an efficiency expert means reading posts like this or attending coaching seminars about topics like this. That’s because you’ve been taught the secrets you can learn have to be handed down from or observed in experts. But these things you’ve been taught are what are called “folk pedagogies”.

"A ‘folk pedagogy’ is a set of beliefs about the best way for people to learn; in effect, what is ‘good’ for them to learn and, in particular, how and why they ‘ought’ to be able to learn it.”(Jones et al., 2004)

Folk pedagogies have been passed down to you and uncritically accepted because you assumed coaches wouldn’t be doing what you see them do if those methods didn’t work or didn’t matter. Let’s start out by looking at a big one.

Folk Pedagogy #1:

The correct coaching objectives are handed down and need not be questioned

This statement is basically the definition of folk pedagogy; it says that what is worth knowing is what more experienced coaches do and/or say is worth doing. When it comes to efficiency, the “best” practices are those in which you see high expectations being met in timely fashion. So you search for experts who have practices that look like that and copy their blueprint. There’s no need to dig any deeper, you can just implement the objectives and methods of their practices and watch efficiency and success just happen. If those are the beliefs you’re working with, then how would the “practice” you want to make more efficient be defined?

When a coach speaks of practice, they are typically relying on the definition above, which is the third definition listed in the dictionary I used. That’s folk pedagogy at work, accepting that “practice” only refers to repeated performance of skills. It’s not wrong to define the word this way, but let’s leave it there for the moment. To be consistent with folk pedagogies, how should you define an “efficient” practice?

Coaches following folk pedagogies typically rely on the first definition that appears, one that describes the efficiency of systems. This definition describes efficiency as a relationship between the energy or effort put into a system and the energy or results that come out of the system as a result. This definition brings up the second folk pedagogy on my list.

Folk Pedagogy #2:

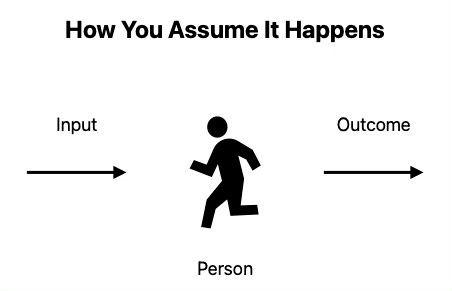

Coaching is a purely technical and systematic endeavor

This statement means that coaches believe they should utilize certain techniques to affect well-understood systems in predictable ways. The developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik summarizes this folk pedagogy as the mentality of the carpenter.

“But essentially your job is to shape that material into a final product that

will fit the scheme you had in mind to begin with. And you can assess how

good a job you’ve done by looking at the finished product…Messiness and

variability are the carpenter’s enemies; precision and control are her allies.”

(Gopnik, 2016)

Viewed this way, coaching becomes neat and clean. You follow the steps outlined by others to get the same results they get. All you need are the right steps and the right tools, which you can get from experts. Once you have those, efficiency is just an equation. If you know the output you want, you can work backwards to find the input you need. At that point, coaching is simplified to just turning the right dial the right amount. That looks something like the diagram below; the connection between input and outcome is clear and consistent.

The belief in that clear connection is the third folk pedagogy on my list.

Folk Pedagogy #3:

Sport obeys the law of cause and effect

As I have written elsewhere, sport is far more complex than cause and effect. Following the law of cause and effect means that, like laws of motion or thermodynamics, if a known action is applied to a known object, then a known effect will result. There is 100% certainty in that connection. Coaches go about their jobs as if that were true but the truth is actually much more complex.

Sport is much more overdetermined and probabilistic. That means there are many inputs, not just the “coaching” you do, that affect a situation. It means there are also many possible outcomes, each with an associated probability of occurring. Just because you see a single outcome does not mean it was the only outcome that could have occurred, nor does it mean the outcome you observed was even the most likely one. Let me offer some proof of that.

In the plot above, each box represents the reception average of a single passer for an entire season of matches. Each blue dot represents a single match reception average. Notice the variance of those dots around any of the boxes. Were the coaches saying the wrong things? Were the coaches saying different things each time? No, they weren’t. Sport is hard. Sport is variable. So how do you let go of that assumed cause-effect connection? How do you let go of the folk pedagogies and find a way to be a great coach? Don’t be a carpenter, be a gardener.

To keep this at a respectable length, I’m creating a bit of a cliffhanger here. Until next time, let me know in the comments what you think gardening has to do with coaching.

How to Make Your Practices More Efficient (part 2)

This is an adaptation of my 2025 AVCA webinar. You can watch the video here.