The Social Learning Social Club

The club you've always been part of without knowing you were part of it

Welcome to the club!

Which club?

The one you already belong to.

How did I get in this club?

The same way all the rest of us did.

How did all of you get in the club?

The same way you did.

Annoyed yet? Don’t worry, I’m not going to explain it. That’s not how social learning works.

When you think of learning, you’re likely to think of school. But the model of learning a subject, like math, isn’t representative of learning a craft, like coaching. And study after study about coach development shows that coaches learn much more by informal means than by formal ones. And yet, your history of formal education - all those years in class - influences how you think you should learn anything, including a craft. You were implicitly taught that being told about coaching is how coach learning should happen. But, as I’ve said before…

Talking isn’t teaching and listening isn’t learning.

But it’s time for a slightly different revelation. I’ve used the movie clip below from “A Few Good Men” before, but in a different context. But this scene also highlights something important and overlooked about learning.

The manuals the lawyers use are examples of formal learning but Lieutenant Kaffee shines a light on what I’m most interested in. The kind of learning the movie clip highlights is social learning. At its roots, social learning theory holds that many behaviors are learned by observing and interacting with other people.

It’s possible to learn some things about coaching by sitting in clinics, reading books and watching videos. But, as I mentioned earlier, research in coach development shows that these kinds of formal learning are not the primary ways coaches learn. Learning socially is a big part of how coaches figure out how to coach. That’s because…

You learn much more than you hear because what’s taught is much more than what’s said.

Much of what coaches learn socially isn’t directly about coaching but it impacts what coaches learn about coaching and it impacts how they coach. In addition to the techniques and drills coaches are intentionally learning, they are also learning how to behave, what to look and sound like, and many other things that aren’t explicitly taught but are part of learning to be a coach. Social learning is happening all the time and the learning started before you were even coaching. You learn that way. Players learn that way…from you.

“…coaching [is] ideologically laden, where athletes were not merely learning technical and tactical lessons but developing attitudes, values and beliefs.”1

The quotation above can only be true because coaches have ideologies that are expressed via their coaching. Your ideology is one of the most important things you have learned and continue to learn via social learning.

I’ve written about the expectation of teaching “fundamentals” above all else. Where did that idea come from? Other coaches. It’s how you saw it done, so it’s what you assumed you were supposed to do. And there’s another thing you learned at the same time: that you are supposed to learn the same way as the athletes you coach. You learned from other coaches that your “fundamentals” are techniques and drills so you should learn those above all else.

Because of that lesson, coaches find themselves focusing so much on learning technique and drills that other areas of coaching aren’t noticed or aren’t considered to be relevant. You learn that techniques and drills are important so you pursue them for years. And then you don’t even notice that when experienced coaches talk about what makes them good at their craft, they never talk about their knowledge of technique and drills. You don’t notice because you’re too busy paying attention to the stuff you’ve already been told is the important stuff. That’s because there’s an even-more important lesson you learn that precedes the lesson about technique and drills. It’s the lesson that makes you think technique and drills are so important.

In an article about teacher development I’ve referenced elsewhere, researcher Deborah Britzman wrote2 that less-experienced teachers believe they “must master the art of premonition and instantaneous response - both of which depend on the teacher’s ability to anticipate and contain the unexpected - to insure control as a prerequisite for student learning” (p. 449). Further, she says “…any condition of uncertainty is viewed as a threat to becoming an expert” (p. 451). This is an expression of the value placed on control in classroom teaching and that value has also extended to coaching.

Control expresses itself in two main ways in coaching, organization and knowledge. Coaches seek to control the environment and, to some extent, players through organization. A coach will be perceived as competent if their practice sessions are seen as being well-planned and well-executed. Having drills for the right occasions aids in the perception of competence. Coaches seek to control situations and, to some extent, players through their knowledge. As Britzman pointed out in her quote above, coaches attempt to use knowledge to counteract uncertainty. Having answers to player questions and explanations for game situations aids in the perception of competence. Because coaches learn that control and competence is important, they pursue things that enhance their ability to project a sense of control, both to themselves and others.

If you learn (socially) that control is important, then you will seek to learn (formally and informally) things that you believe will help you be in control. This illustrates my point about social learning impacting what you learn and what you do as a coach. No coaches I’ve encountered have explicitly said that control is important. And yet, the majority of them learn and coach in ways that reaffirm that exact belief. Coaches learn (socially) ideas about what it means to be a “good” coach, so they seek learning opportunities (formal and informal) that help them pursue being “good”.

I have a problem with this.

I don’t have a problem with coaches wanting to be good at their craft. I have a problem with the unexamined premise of what “good” is. In many cases, what is “good” is what’s been done before. It’s not good, it’s understandable. You can explain what you’re doing to others. In many cases, what is “good” is what coaches you admire did. It’s not good, it’s a model to follow, in the absence of building your own model.

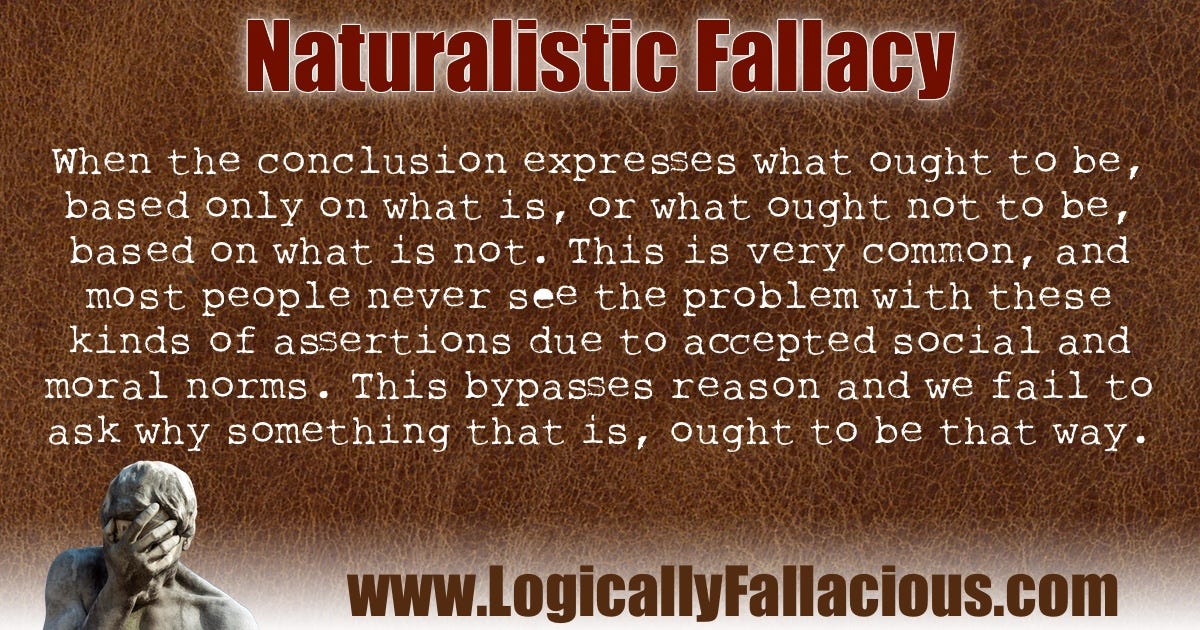

To get philosophical for a moment, I have a problem with this because it is an example of the is-ought problem, also known as the naturalistic fallacy.

Coaches assume that what is done is what ought to be done to become a “good” coach. The truth is that, using current methods, becoming a “good” coach happens much more by coincidence than by will. Why should you do things the way you saw them done? Because that’s what you learned from the society you’re in, not because it’s a proven method for coaching excellence. That, for better or worse, is how social learning can affect your learning and coaching.

Doing things the way they’ve always been done is a terrible reason to do anything. And yet, that’s the basis for much of what you learn socially. Social learning is how many norms are passed on and that process has been very helpful in many situations throughout history. But I think many coaching norms passed on through social learning don’t have good reasons for being passed on. The examples I gave above of learning drills and techniques are only two. I can explain how these norms came to be passed on but I can’t explain why.

I can, however, offer suggestions on how to make social learning work for you. It’s not about reflexively rejecting previously unquestioned norms. It’s about productively questioning those norms. One important question to ask is what following those norms allows you to be (and prevents you from being) as a coach. Another important question to ask is what following those norms allows you to do (or prevents you from doing) as a coach. As I mentioned above, the answer to the latter question is often that it allows you to fit in. I’m not sure that’s a great reason to coach a certain way.

If you don’t think that’s an adequate reason to coach in a certain way either, then it’s time to ask a different set of questions. Who do you want to be as a coach? What do you want to do as a coach? How do you want players to experience you as a coach? These questions are about your values, which can be thought of as your personal norms. Your values are still things you learned socially but also developed for yourself. They are also things you teach socially. They comprise the ideology, the “attitudes, values, and beliefs” I quoted above, that athletes are learning from you.

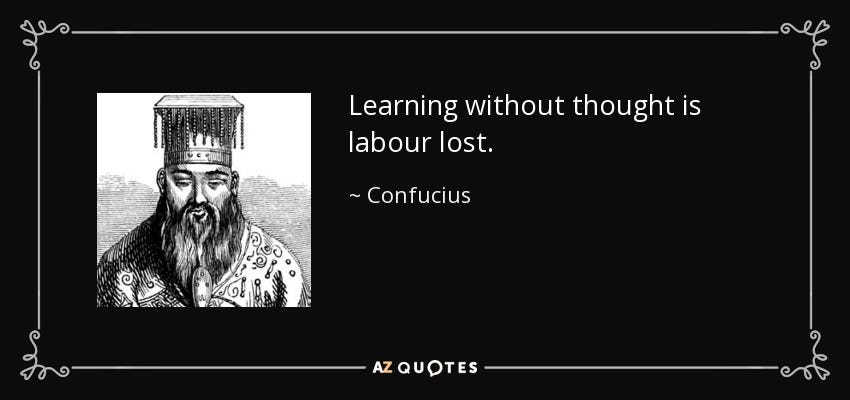

So social learning is clearly not the problem with coach learning. The problem is any kind of learning done without thought. The problem is assuming that how things are is how things ought to be. That leads to doing work in the name of conformity. I think that’s what Confucius was warning against because that work doesn’t bring you closer to anything of meaning, it’s mistaking change for progress. You learn (with thought) so you can do better work with more meaning.

All of that sounds nice, but there’s substantial pressure for coaches to fit in. There’s a need to do what others have done and are doing. The necessity you feel is a product of not wanting to explain why you’re doing it differently. The necessity you feel is an expression of how much society values and prioritizes social understanding and acceptance.

That desire to feel understood and accepted is real. I’m not saying it shouldn’t exist. I’m saying you can be understood and accepted while being different. If you look, there are coaches all around you that do things differently. What are they teaching you? What are they trying to do? Who are they trying to be? What do you have in common with them? How do you want to be different from them? This is how you think your way through social learning.

Social learning happens everywhere in coaching, so it’s important for you to understand social learning because of how it impacts your learning as well as your coaching. To take control of that impact, you should thoughtfully approach your learning. Thoughtfully learning means asking questions that help you define the norms and values affecting you. Thoughtfully learning means choosing norms and values that reflect who you want to be as a coach and what you want to do while coaching. There’s no doubt this takes work and attention but your efforts will result in better, more meaningful coaching than if you had spent the same energy pursuing techniques and drills in an unexamined way.

Jones, R. L., Potrac, P., Cushion, C., & Ronglan, L. T. (2010). The Sociology of Sports Coaching. Routledge.

Britzman, D. (2011). Cultural Myths in the Making of a Teacher: Biography and Social Structure in Teacher Education. Harvard Educational Review, 56(4), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.56.4.mv28227614l44u66